Funicular railways aren’t common in Canada and they are even less common in the Prairies but the steep banks of Edmonton’s North Saskatchewan River turned out to be the perfect place.

So Alberta’s second largest city now boasts a multi-award winning funicular, joining a mere handful of others in Quebec and Ontario.

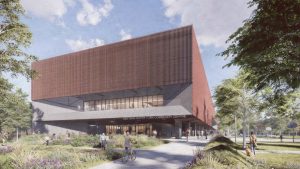

Edmonton’s Mechanized River Valley Access is a marvel of structural steel engineering at a difficult location which rises 50 metres. It also incorporates a 19-metre cantilever lookout, named after Frederick G. Todd, a landscape architect who proposed a River Valley park system in the early 1900s, elevator, and stairs.

It has won seven awards including a Canadian Institute of Steel Construction (CISC) 2018 Engineering Award and an International Architecture Award from the Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design and the European Centre for Architecture, Art, Design and Urban Studies in the bridges and infrastructure category.

Funicular cars run on tracks and are powered by a looped cable and usually travel a short distance up a slope carrying passengers.

The Edmonton Mechanized River Valley Access opened in December 2018, connecting downtown to the scenic River Valley trail and recreation area. It incorporates a staircase and accommodates bicycles, strollers, wheelchair users and mobility scooters, carrying up to 20 people at a time.

While it draws power while climbing, it uses regeneration technology to power itself on the downward run.

The $24 million project, which also includes a new pedestrian bridge across Grierson Hill Road, was designed by DIALOG which has had a hand in several public projects in and around Edmonton.

“We saw a rather pragmatic need to connect the River Valley to downtown Edmonton,” says Jeff DiBattista, structural engineer and practice principal at DIALOG. “We also saw an opportunity to deliver a journey that was beautiful.”

That vision ties in the renaissance of downtown Edmonton, once mocked as “deadmonton.”

The Walterdale bridge, the new library, the massive mixed-use Edmonton arena district (ice) project and the ongoing discussion for an urban gondola — the Prairie Sky project — as a rapid transit mode to carry commuters across the River Valley have steadily added to the city’s skyline and points of interest, indeed, as has the Mechanized River Valley Access.

The team started with a design charette with local stakeholders and then held one of their own internally, bringing on colleagues and others from other areas of speciality engineering, such as mechanical engineering, from across Canada.

“It wasn’t part of the budget but it was something we wanted to do,” DiBattista says. “We also looked at Switzerland for expertise in funicular railways because it’s not something we had experience with.”

With the concept taking shape, steel quickly emerged as the right material for a variety of reasons, he says, one being that steel can be especially elegant given the right application and design. Paired with the specially finished wood steps, it’s a delight of form and function.

Steel also allows the bridge to be supported without bearings or deck joints at the elevator shaft because the columns can deform longitudinally to accommodate thermal expansion and contraction.

“By using steel for the bridge superstructure, we were able to extend the bridge cantilever a significant distance into the river valley, while minimizing our physical footprint on the valley floor,” DiBattista says. “Case in point, a tree still stands directly below the 19-metre-high cantilever; careful erection procedures helped us make this possible.”

Also, he says, steel was the best choice when it became clear weight would be a design challenge. The entire structure sits on the steep bank of the river and with no bedrock to tap into, the design team opted to set the concrete support piers with helical screw piles.

“We needed to keep the weight down because we didn’t want to destabilize the bank and cause problems,” DiBattista says. “It also kept the heavy equipment we had to use to a minimum.”

The project rolled out smoothly, he says, and while there are always challenges none were out of the ordinary or caused major delays.

“We really want to give a shout-out to acknowledge our partners on this project, the city of Edmonton, who worked early on to get the land rights because at the top we were on Fairmont Hotel and McDonald’s property and it allows us to change the design to make it better,” he says with nods to Norfab Manufacturing and Supreme Steel. “And construction manager Sam Johnson from Graham Infrastructure was so important to this.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed