Winter roads are key to survival for many isolated communities in northern Canada. Oftentimes, they’re the only way in and out. But, with climate change and warmer winters they’re becoming less safe.

Paul Barrette, a research council officer at the National Research Council in Ottawa, is working with a team of federal scientists to figure out a way to keep the thoroughfares open longer as the climate warms.

Specifically, the mandate of the team is to devise and test methods to reinforce the winter roads so that their operational lifespan can be increased and, at the same time, decrease the potential for mid-season closure.

“Winter roads are only used for a few months each year in the North and the communities are isolated without them,” explains Barrette. “They are used to bring in fuel and construction materials and other commodities. They rely on this time window and thanks to winter roads they get this material.”

There are roughly 10,000 kilometres of winter roads in Canada. They’re mostly on land, but there are sections that cross rivers or lakes. Such over-ice segments are most vulnerable. Cold temperatures are required to grow the ice to a safe thickness, but with warming the ice is sometimes not as rigid as it should be.

Barrette and the team have been looking at effective ways to stiffen the ice with materials such as wood pulp, steel cables and polypropylene mesh frozen into the road.

By reinforcing the ice with an artificial membrane, it doesn’t need to be as thick and can resist the larger weight at the bottom of the ice cover. Such a method should prevent an actual breakthrough, even if there is some fracturing in the ice.

We know they work in the lab, but the challenge is deployment and retrieval,

— Paul Barrette

National Research Council

The team is using both physical tests and numerical modelling to explore the implementation of such material on actual ice roads as well as addressing all aspects of the material, including availability, cost, adequate mechanical properties, and ecological suitability. The team is also looking at the feasibility of deployment and retrieval to decide the best candidates for target locations to test the products.

Logs have been used effectively in real operations, along with branches, but there aren’t trees everywhere in northern Canada and environmentalists may also object to cutting trees every year, says Barrette, “so we need to think of another way of doing things and there are materials out there that work.”

Since the 1940s, a variety of different reinforcing materials have been incorporated into ice to improve its resistance to fracture and make it stronger.

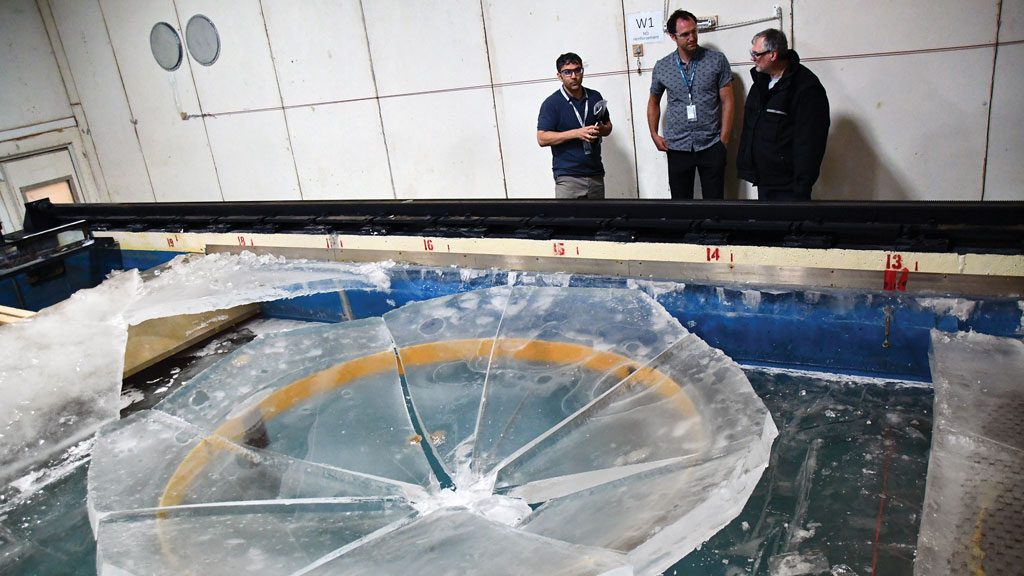

Barrette and his team have been testing the wood pulp, steel cables and polypropylene mesh in the lab — a large refrigerated chamber with a tank like a large swimming pool that allows pressure to be applied to material embedded in ice — and have found they do make the ice stronger.

The research is funded by Transport Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and the Arctic Program. The research team consists of Barrette, Lawrence Charlebois, Bradley Butt and Hossein Babaei.

The key now, says Barrette, is for researchers to do more testing to figure out what materials are best suited to actual use in the field and can withstand the elements and traffic, but are also compatible with the environment.

“That’s what we’re doing in the lab just now. We know they work in the lab, but the challenge is deployment and retrieval. The idea is to think of a way of deploying it and retrieving it in the field,” he says.

Within the next two years, Barrette hopes to conduct a pilot study to test the materials on actual winter roads. Such testing would include controlled loading and breakthroughs.

The testing thus far has shown that reinforcing the roads will increase the predictability of their load-bearing capacity and of their capability to sustain vehicle weight. It will also reduce the thickness needed to make the ice roads safe to cross, an important consideration due to the impacts of climate change.

However, says Barrette, while reinforcement is achievable the deployment and retrieval of the materials is still the biggest challenge.

Stakeholders also have reservations about embarking on such a venture because sections of winter road that cross water would need to be broken up so the material can be inserted.

“Stakeholders are a little reluctant to go with a solution like that and understandably so,” he says, “because what you’re saying to them is, ‘We can reinforce the ice, it doesn’t need to be as thick, and you no longer have to go through breakthroughs.’ But it’s never been used before, so that’s where the reluctance comes from. That’s a bit of a challenge also on top of the deployment and retrieval challenge.”

The NRC has several other projects on the go related to winter roads. One is a reconnaissance and exploratory project to identify winter roads in the North, mainly Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, that are weak links and get more information about who uses them and what goods are transported on the roads.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed