The City of Toronto’s largest-ever infrastructure construction project isn’t something many residents will notice. That is because much of it is 50 metres underground.

The Coxwell Bypass Tunnel (CBT) is a part of an ambitious program by the city to eliminate sewer and water outflows into Lake Ontario.

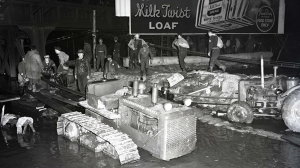

The tunnelling section is being done with a boring machine, nicknamed “Donnie,” that is cutting a 6.3-metre diameter passage through bedrock from the Ashbridges Bay Treatment Plant (ABTP) to Coxwell Ravine Park 10.5 kilometres away, says Samantha Fraser, manager for the project for the City of Toronto.

About 30 per cent complete, the tunnel commenced after Donnie was transported unassembled via barge and truck to the plant about a year ago. Since then, the big boring machine has dug up to 30 metres a day, heading west along Lake Shore Boulevard to the Don Roadway, she says.

It will eventually go north to the North Toronto Treatment Plant East and by late 2023 is expected to terminate at the Coxwell park.

One of the reasons the tunnel is so deep at 50 metres below grade “is to avoid a bedrock valley (soft ground conditions) below the Don River,” Fraser points out.

The 110-metre-long tunnel borer weighs almost 1,000 tonnes. Manufactured by Lovsuns, it was purpose-built for the project, she says.

Donnie’s cutter head is comprised of multiple bits designed to grind the bedrock. As it bores, it places rings of pre-cast concrete segmental liners by a “vacuum articulated process” around the tunnel, says Simon Hopton, the city’s director of design and construction for the project.

The ground bedrock known as “spoil” is being transported on a conveyor back to the surface. Some of the spoil will be used as fill in a “landform” development for a high-rate treatment facility at the ABTP, Hopton points out.

The big boring machine works about 20 hours a day using crews in two shifts. The CBT is being carried out by consortium North Tunnel Constructors ULC.

The project also includes five shafts 50 metres deep by 20 metres wide which will serve as storage and management of stormwater. A dozen smaller drop shafts will also help manage stormwater flow into the tunnel network, says Fraser.

The tunnel is the first of three phases of the 22-kilometre Don River and Central Waterfront Wet Weather Flow System, which will keep combined sewer overflows out of the city’s waterways.

Along with capturing the water in the tunnel and storing it until capacity is restored, the flow will be transported for treatment through an ultra-violet disinfection facility at the ABTP, Fraser says.

The water will then be discharged through a new 3.5-kilometre outfall into Lake Ontario.

Hopton says integrating all the projects is a big engineering hurdle because of the scope of work and the fact different design consultants are retained on the development.

But he adds that along with the environmental benefits of the CBT and the overall Central Waterfront flow management program, the city will see a cleaner lake resulting in improved recreational opportunities for residents.

Including the Coxwell tunnel, a new outfall, pumping system, disinfection treatment and Ashbridges Bay remediated land, the budget is more than $3 billion.

Currently the project is funded by the city of Toronto’s water ratepayers, says Fraser.

Recent Comments