Part one of Cracks in the Foundation: Mental Health, Substance Use and Construction, examines the current state of substance use across the country, with experts painting a picture of how the industry has been specifically impacted. The third article in this DCN-JOC Special Feature Series delves into the numbers in Western Canada as the situation in B.C. and Alberta continues to escalate.

Contractors, supervisors, industrial trades, electrical trades, machinists, metal forming workers, plumbers, pipefitters, carpenters, cabinetmakers, masons, plastering trades, crane operators, drillers, blasters — these are just some of the workers dying in Western Canada from opiate use.

By the numbers

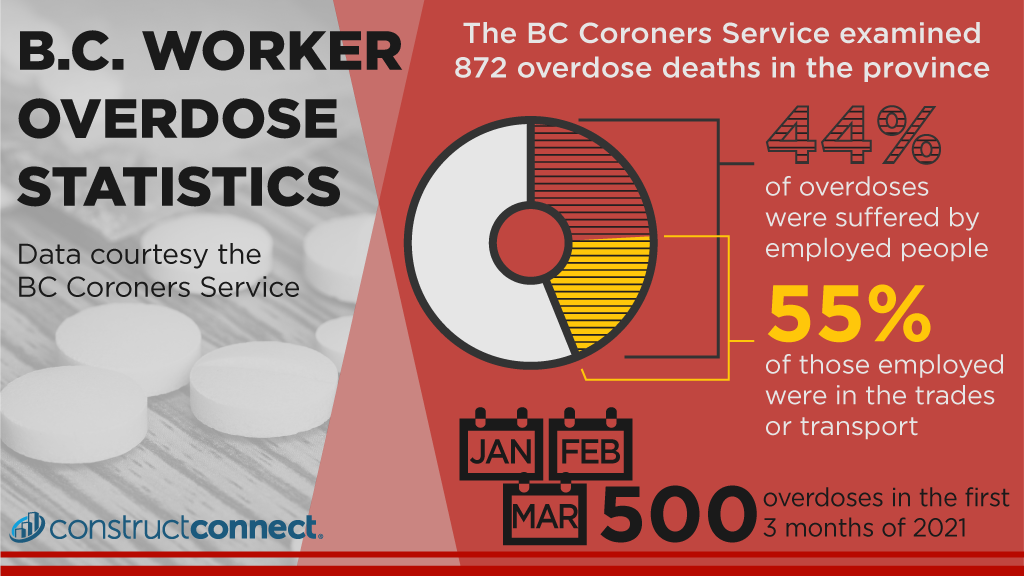

An in-depth analysis of 872 overdose deaths from the BC Coroners Service showed that 44 per cent of people were employed at the time of death and of those employed, 55 per cent were employed in the trades and transport industry. The vast majority of these deaths were men in their 30s and 40s using alone.

The report came after officials began to notice overdose deaths beginning to spike. In B.C., drug overdose deaths increased from 211 in 2010 to an estimated 1,450 in 2017. The spike prompted the provincial health officer to declare a state of emergency.

The problem has persisted. In the first three months of 2021, nearly 500 people died from a drug overdose.

And it’s not just impacting B.C.

According to report by the Province of Alberta, trades, transport and equipment operators made up 53 per cent of drug overdose deaths of those who were employed.

In the U.S., drug overdoses are also slamming the construction sector.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that examined unintentional or undetermined overdose deaths in 26 occupation groups found construction occupations had the highest proportional mortality rates of deaths from both heroin and prescription opioids.

Toxic supply

“I think in days of old you thought that buying illicit substances, you would get what you thought you were getting,” explained Dr. Sandra Allison, a medical health officer for Island Health, B.C.’s health authority on Vancouver Island and its surrounding communities.

She explained lab reports are showing methamphetamine and cocaine often contain powerful synthetic opiates like fentanyl or powerful sedatives like benzodiazepines.

“We don’t have a timely or accessible drug testing or checking approach,” said Allison. “What we see is individuals who thought they were getting something stimulating like meth or coke and it’s been contaminated with stuff that brings you down, like strong synthetic opioids or benzo analogues.”

Allison said Island Health’s overdose prevention sites often see users sedated for hours. When benzos and opiates are combined, users can stop breathing and die.

“It’s very dangerous if someone is using alone and they overdose,” said Allison. “And naloxone only reverses the effects of opioids. Something like fentanyl can require many doses of naloxone. The things in the drug supply are always changing.”

Allison also noted underlying the death statistics are many non-fatal overdoses or near overdoses that can cause horrible damage similar to a brain injury.

The perfect storm

“We knew things were quite bad,” said Vicky Waldron, executive director of Construction Industry Rehab Plan (CIRP). “But the question is why?”

CIRP provides free alcohol, drug and mental health treatment for the organized construction industry in B.C. Waldron says she doesn’t have all the answers, but she believes there are several elements that have created a “perfect storm.”

First, construction tends to be male-dominated when compared to other sectors and data from the province shows the majority of overdose deaths are men. Second, construction can be a physically demanding career with lots of injuries. Finally, you have a culture that stigmatizes men who admit they are in physical or emotional pain. Mix in a critical shortage of workers and pressure to get back to work and you have an industry heavily represented in overdose deaths.

“You tie all this together and it’s the recipe for what is going on,” said Waldron. “We have a society that values people powering through things. We don’t value someone who takes time off and there is a stigma around men taking time off. There is a lot of machismo in this.”

Waldron said the extent of the substance use in the industry is staggering. According to CIRP’s research, one in three construction workers across the country — union or non-union — reported “problematic substance abuse” and one in two stated they felt like they had mental health issues they were struggling with.

“A high proportion of these folks said they won’t tell anyone because of stigma,” said Waldron. “But they are saying ‘I think I’ve got an issue’ and for me that is just heartbreaking.”

User profiles

The Vancouver Island Construction Association (VICA) dug even deeper with their research, partnering with Island Health to conduct extensive interviews with users. They found interviewees fell into three different profiles.

Profile A started construction when they were young and began using drugs and alcohol for fun as part of a “work hard, play hard” mentality. However, in some cases the casual drug use grew into a larger problem if mental health issues arose, often from high stress, burnout or feeling overwhelmed.

Profile B is someone who works in construction but sustained an injury and was prescribed opiates for pain management. But the medical use grew into substance abuse. The report noted continued drug use was often fuelled by a strong desire to return to work, despite being in pain.

Profile C is someone who experienced severe trauma and began using drugs to cope. The dual effect of trauma and substance abuse reduced their capacity to maintain regular employment and they joined the construction industry, often as a labourer, in order to have flexible, low-barrier work.

Rory Kulmala, CEO of VICA, explained some themes crossed all profiles.

“Regardless of profile, there is a reluctance to seek help, particularly in the male demographic, for health, mental health or wellness in general,” he said, adding living up to ideas of masculinity caused many to internalize physical and mental pain.

“They don’t want to be seen as weak.

“I think it’s about working on dispelling the stigma and creating an environment where people can seek help in a safe way. We need to dispel the myth that employers don’t care and only want the job to get done.”

*The fourth and final article in part one of this special feature series, being released Sept. 10, will take a look at the situation in the U.S. and the lessons being learned south of the border.

Follow the author on Twitter @RussellReports.

Recent Comments