The idea of a timber skyscraper gracing London’s skyline may have taken a step closer to reality earlier this year, when conceptual plans for an 80-storey, 300-metre tower were presented to the city’s mayor.

Michael Ramage, of the University of Cambridge and Kevin Flanagan, a partner at PLP Architecture, presented the renderings to Boris Johnson, who at the time was still mayor of London. He has since been appointed British Foreign Secretary in a government re-organization.

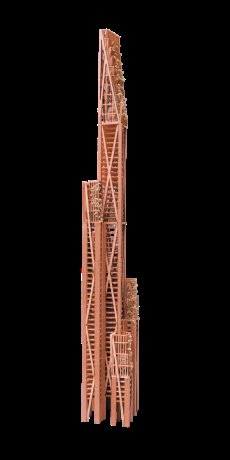

The renderings show a tall, slender timber-framed structure rising from an area known as the Barbican, a large residential complex designed and built in the 1960s and 70s.

The conceptual proposals include creation of more than 1,000 new residential units in a mixed-use tower and mid-rise terraces. The tower would enclose a million square feet.

Ramage is director of Cambridge’s Centre for Natural Material Innovation. He said the proposal was developed to be superimposed upon the Barbican "as a way to imagine what the future of construction could look like in the 21st Century."

He said the city needs to increase population density if it is to survive over the long term, and one way of doing that is by building taller buildings.

"We believe people have a greater affinity for taller buildings in natural materials, rather than steel and concrete towers. The fundamental premise is that timber and other natural materials are vastly underused and we don’t give them nearly enough credit."

He noted that, in London, "nearly every historic building, from King’s College Chapel to Westminster Hall, has made extensive use of timber."

But the renderings made public are conceptual. Is the tower—dubbed the Oakwood Tower—ever go up?

In an email exchange, Ramage said it’s "unlikely the project will ever be built as it is right now."

"The purpose of the project is to demonstrate the feasibility of tall wood buildings at the largest scale, so we are taking specific structural connections and details from the design and testing them in our labs at Cambridge University."

Oakwood Tower isn’t the only tall timber structure in the works. It is only the first in a series of four timber skyscrapers developed as part of the Cambridge Supertall Timber Project. Two of have already been designed: The Oakwood Tower and another, in Chicago, designed with the Chicago offices of Perkins + Will and Thornton Thomasetti.

Reaction so far has been encouraging, Ramage wrote.

When the conceptual plans were presented to Johnson, "the idea was well received."

"Members of the Greater London Authority were there who weren’t politicians," he wrote, adding that "we are drafting a policy brief on the benefits of massive wood construction."

He also said that there has been no effort to cost the Oakwood Tower, "but it has been designed with typical commercial constraints and sizes for London."

Among the documents presented, was one lauding timber as "a lightweight and sustainable substitute for traditional construction materials, which could also help to speed construction times and reduce carbon emissions."

And a statement from Cambridge noted that "the use of timber as a structural material in tall buildings is an area of emerging interest for its variety of potential benefits; the most obvious being that it is a renewable resource, unlike prevailing construction methods which use concrete and steel."

A persistent worry about fire is one that must be overcome if tall wood structures are to gain a foothold in the marketplace. That’s why the conceptual design for Oakwood Tower is engineered to meet the fire regulations currently in place for concrete and steel buildings.

The engineering firm of Smith and Wallwork was part of the design team, and the company’s Simon Smith said the timber "is our only renewable construction material, and in its modern engineered form it can work alongside steel and concrete to extend and regenerate our cities."

Engineered wood is central to the Oakwood Tower, which makes extensive use of both cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glue-laminated (Glulam) timber.

But Ramage and his Oakwood Tower team are by no means the only design professionals contemplating large-scale use of modern engineered timber.

Dalston Lane, another London project, will use more than 3,000 cubic metres of CLT. It has been estimated that the 121-unit development will use more timber than any other project in the world, making it the largest CLT project globally. The project will enclose more than 12,500 square metres of residential space and about 3,500 square metres of commercial space.

The architect is the British firm of Waugh Thistleton. And the firm’s Andrew Waugh has called the project "the beginning of the timber age."

Wood, he said is "super-fast, super-accurate, and also makes the most amazingly beautiful spaces."

"These are buildings that feel very good to be in, very robust, and very solid."

Wood enthusiasts seem to be popping out of the woodwork in many places.

"CLT is the future of construction. Timber is the new concrete," says Alex de Rijke, director of the London-based firm dRMM, which has been working with the material for a decade.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed