More than 40 years after its grand opening, the CN Tower remains remarkably relevant: an engineering marvel, a major attraction and an irreplaceable part of the Toronto skyline.

The city has seen major construction projects before and since, but not one so visible that almost every citizen could mark its stunning progress as it rose from the city’s downtown.

The CN Tower was conceived as only one feature of a complete redevelopment of the Railway Lands owned and maintained by the Canadian National Railway. Ultimately, it was the only feature of the Metro Centre development that was realized.

There was a solid reason for building the tower—radio and television signals were no longer reaching the city unimpeded, thanks to rapid highrise expansion. At a little over 1,815 feet, the tower could beam signals of all sorts to Canadian markets and across Lake Ontario to the United States. However, part of the reason for the project was a simple act of will, demonstrating to the world what Canadian architects, builders, engineers and corporate clout could achieve.

Major contributors to the project team included: NCK Engineering (structural engineer); John Andrews Architects; architects of record, the Webb, Zerafa, Menkes, Housden Partnership (now WZMH Architects); The Foundation Company of Canada (now part of AECON); steel fabricator Canron (Eastern Structural Division); Scanada Slipform Systems Inc.; and excavation contractor Rumble Contracting Inc.

The most detailed history of CN Tower construction has been researched by Robert Lansdale, historian and curator at PastAndFutureHistory.com. Lansdale continues to chronicle every aspect of construction, including the names of individuals who worked on the project and personal interviews with them. His current labour of love is a complete frame-by-frame restoration of the last known pristine copy of a 16mm film on construction of the CN Tower produced by Canron.

“I have been working on the CN Tower project for decades and expect to finish it in 30 years’ time,” he says.

Lansdale notes that the initial pitch for the CN Tower imagined a budget of $12 million, a significant underestimation.

Construction began on Dec. 8, 1972 with demolition and clearing of existing railroad infrastructure—and no building permit. Other milestones followed in rapid succession. Excavation of the foundation to bedrock began in February 1973 as crews removed more than 56,000 tonnes of earth and shale. Foundation work began in March on a concrete-and-steel foundation 6.71 metres deep. The foundation comprised 7,046 cubic metres of concrete and 453 tonnes of reinforcing steel. The foundation was completed in May.

Concrete pouring on the tower began in June using a sophisticated slipform supported by a series of hydraulic-powered climbing jacks. Pouring was a 24-hour-a day operation. As each layer of concrete cured around rebar, the slipform was raised and adjusted according to the design contours. Concrete in the tower was single-sourced and mixed on site to ensure uniform consistency. Lansdale notes the concrete was hand poured using wheelbarrows around the periphery of the structure.

A single crane rode slowly up the concrete tower as it ascended.

Only when the tower reached 300 feet did the city issue a building permit.

An article written by CN Tower engineers appeared in a 1976 issue of the Precast Concrete Institute Journal and describes the difficulty of engineering the post-stressed tensioning cables that helped to strengthen the tower. The cables were fed downward through ducts by a hand-controlled reel system to the tower foundation. The cables had to be protected from moisture and tensioning operations were scheduled around slipform work. While most cables were tensioned from below using hydraulic jacks, some had to be tensioned from the top of the building, resulting in scheduling conflicts.

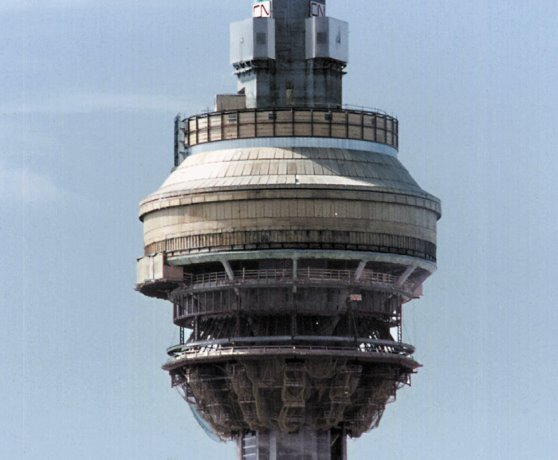

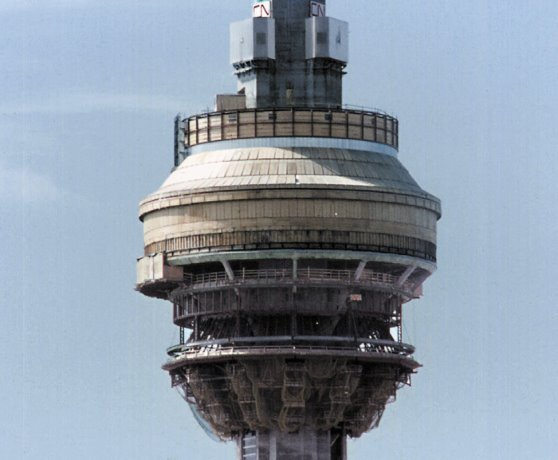

Slipform work was completed on Feb. 22, 1974 when the tower reached 1,464 feet. Work on the SkyPod came next, as concrete forms and tonnes of steel were lifted into place and assembled. This work included construction of the revolving restaurant and the Radome, the fabric ring containing telecommunications equipment.

Some of the most iconic photos of the tower’s construction feature “Olga” a Sikorsky S-64 helicopter operated by Erickson Skycrane of Oregon. The project’s most dramatic moment occurred as the chopper attempted to remove the crane, which seized on the supporting bolts, tethering the helicopter. Steel workers quickly arrived on the scene to burn off the bolts as the helicopter hovered nearby. Olga ultimately delivered the crane to terra firma with only 14 minutes of fuel left.

Subsequent placement and bolting of the 44 antenna segments proceeded smoothly. The final segment of antenna was bolted into place on April 2, 1975, officially making the CN Tower the world’s tallest free-standing structure.

Subsequent placement and bolting of the 44 antenna segments proceeded smoothly. The final segment of antenna was bolted into place on April 2, 1975, officially making the CN Tower the world’s tallest free-standing structure.

The CN Tower opened to the public on June 26, 1976. The project cost $63 million to build — about $325 million in today’s currency, accounting only for inflation — and employed the labour of more than 1,500 workers. It contains 40,500 cubic metres of concrete, and almost 5,100 tonnes of steel.

John Andrews, Ned Baldwin and Roger du Toit were part of the architectural design team working on the tower at John Andrews Architects. Andrews, now 84, has long since returned to his native Australia after working on a host of significant Canadian projects. Ever mindful of his connection to the CN Tower, he’s still fiercely proud of his design for Scarborough College (1963), the project that first brought him recognition.

“But I was so excited doing design work on the CN Tower that I still get a chuff out of it,” he says.

He recalls two or three different designs. The approach represented on the original models of Metro Place features three slim cylinders placed in an equilateral triangle —one to contain stairs, another an elevator and a third pipes and ducts. They would be interconnected by horizontal tubes, and topped by antennas and an observation deck.

“The one we built had the lifts on the outside, which is still quite a scary experience for some people,” Andrews says. “The tower was also designed to sway somewhat. If you fix your eyes on something, you can actually perceive the movement of the tower as it sways in the wind.”

One of the project’s biggest challenges was preventing the formation of ice on the tower. Russia had already built the Ostankino communications tower at 1,772 feet tall, but in Cold War days, connecting with colleagues behind the Iron Curtain involved layers of protocol.

“I attempted to get in touch with them through the Department of Foreign Affairs, but ultimately I just wrote to the guy who designed it and he wrote back,” says Anderson.

“We built the donut that encases all of the communication antennas out of plastic and any heat that comes from the machinery is collected in there to keep it warm. Heat is also pumped into the steel needle.”

Robert Sampson, principal at WZMH Architects was a teen when the CN Tower was completed. But the firm’s connection to the project remains strong. It still retains original sketches of the tower through conception.

“It’s great to have the CN Tower in our portfolio because it’s so well known around the world,” he says. “But we don’t want it to completely overshadow the many buildings our firm has contributed to the city’s downtown. We promote it, but we do it sparingly, often using it as the very last slide in a presentation of our portfolio without talking about it.”

He notes that the tower could be built stronger and taller today. However, Toronto no longer requires a single, massive telecommunications tower — that makes the design a unique reflection of its place in history.

Given the ability to change anything about the CN Tower, Sampson is hesitant.

“I would keep the tower as is,” he says. “I think it’s a great design that simply looks very good. I would only change what happens at the ground level. There’s a bit of a circuitous maze through dark corridors to get you to the elevators. I always find that a bit disorienting.”

In 1995, the CN Tower was voted one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers. This year the CN Tower (and the Ontario Place Cinesphere and Pods) were presented with the 2017 Prix du XXe siecle by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, in partnership with The National Trust for Canada. The award recognizes projects for their enduring excellence and national significance to Canada’s architectural legacy.

Toronto alderman Elizabeth Eayrs is famously quoted as telling city council: “We’ll live to regret it if we let this monstrous dart go up.” But today, Eayrs explains the context for her remark.

“It was a single building representing one company and it seemed very obtrusive,” she says. “I didn’t want one corporation to dominate a skyline that had a very low profile at the time. I’ve lived long enough to become totally used to it. Today, the CN Tower has become Canada’s tower.”

Main Pod of CN Tower under construction.

Photo: ROBERT TAYLOR/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed