The Toronto Zoo has developed a reputation for considering the welfare of its animal residents first. That mission underscored the development of the zoo from its planning stages and into the construction of its naturalized animal habitats. However, while much of the zoo relies on earth, stone and wood to achieve that vision, two steel-and-glass structures — the African Rainforest Pavilion and the Indo-Malaya Pavilion — are among the zoo’s most recognized and iconic buildings.

The zoo was conceived to replace Toronto’s Riverdale Zoo, founded in 1888 around the donation of a single deer. However, the original zoo was rapidly running out of room in its constrained location along the Don River. Talk of a new zoo had begun mid-century, but picked up steam in 1966 when an 11-citizen group formed the Metropolitan Toronto Zoological Society. Metro Council approved the use of a parcel of land in Scarborough the following year.

Clearing and grading of the zoo site began in 1970. Gunter Voss was appointed zoo director that same year and insisted on one of the principles that made the zoo unique. It was the world’s first zoo to be divided into “zoogeographical” regions with pavilions and areas devoted to each area of the globe.

The individual buildings and pavilions that make up the zoo were designed by a consortium that included Ron Thom Architects, Clifford Lawrie Bolton Ritchie Architects, Crang and Boake Architects and Yolles Engineers.

“The zoo was revolutionary in many ways, because it was designed to be animal-centric,” says Adele Weder, architecture critic and curator of the exhibition, Ron Thom and the Allied Arts, which recently traveled Canada. “In traditional people-centric zoos, spectators gawk and gaze at captive animals in cages. This zoo was conceived and designed expressly to replicate or evoke the natural environment and landscape in which the animals would normally be found.”

Thom had achieved considerable acclaim for his work on the University of Toronto’s Massey College and Trent University’s riverside campus.

“They wanted a brand name architect attached to the project,” says Weder, who is working on a definitive biography of Thom. “But the type of work he had become famous for was costly. He was a difficult man to work with and his architectural ambitions were expensive to realize.”

Weder notes that Thom’s work was primarily limited to the two pavilions, while other consortium members developed the remaining structures. Both of Thom’s buildings relied heavily on steel construction.

“He wasn’t a fan of steel in particular as a construction material,” says Weder. “He trained as an artist and thought of architecture as an art and preferred to work with wood and organic materials. He needed steel to realize the design that sprung from his imaginative mind — cantilevers and special framing and rebar. Steel was simply the best material to make the project viable.”

Weder notes that Thom preferred to avoid the rigid geometry of exclusively right-angle design. The pavilion roof lines make considerable use of 60-degree, 30-degree and 90-degree angles to create the impression of undulating slopes and curves — hyperbolic paraboloid structures.

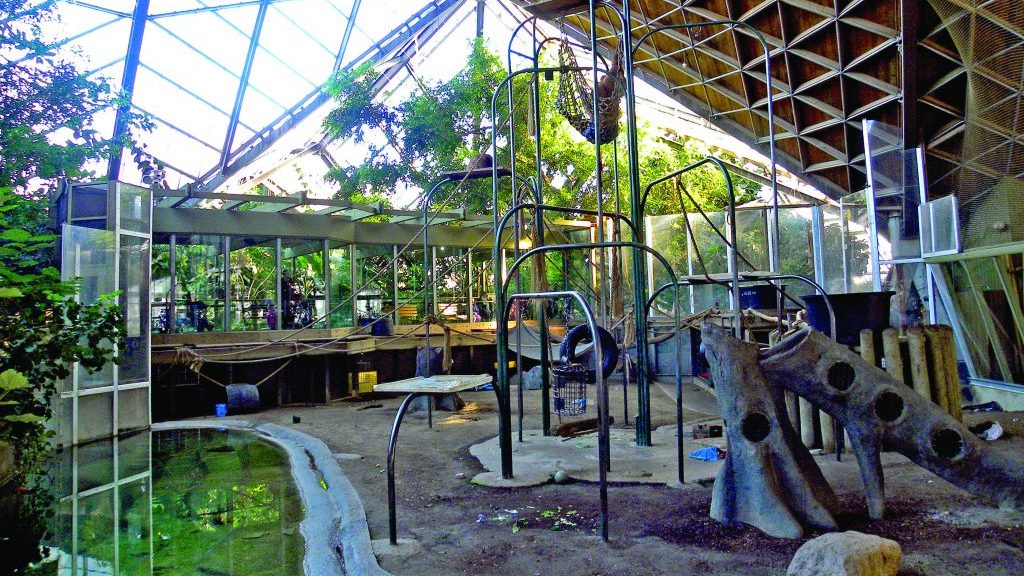

The roofs of both buildings are supported by structural steel set on concrete columns. This framing provides support for the large amount of glass used in the building roofs, providing natural light for animals. Secondary steel grids further support the glazing. Opaque roofing is supported both by structural steel and by a triangular steel grid made of hollow tubing. All of the steel and connections are made visible by design.

About 600 members of the public accepted an invitation to view the zoo under construction on September 16, 1973 for the admission price of a quarter. The Toronto Star reported that the most interesting animal on the site was a horse belonging to a mounted police officer, but zoogoers were…“visibly impressed by two great triangular-walled pavilions whose 100,000 square feet will contain tropical plants and rare animals from Africa and Indo-Malaya.”

The zoo opened on Aug. 15, 1974. While cedar roofing has long ago been replaced by more durable copper, the two pavilions continue to stand, braced by steel, almost exactly as they were designed and built almost 50 years ago. While human visitors might notice the unique designs of the pavilions, the tapirs and gorillas inside simply accept them as their environment — just as the building designers intended.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed