As it was created by Canada’s first inhabitants, it would seem appropriate the lounge of the new Odeyto multipurpose centre at Seneca College’s Newnham campus in Toronto is shaped like a resting canoe.

Designed in a joint venture by Gow Hastings Architects and Two Row Architect — a practice based on the Six Nations Reserve — and built by general contractor Mettko Ltd., the centre is an administrative and cultural facility serving the college’s Indigenous students.

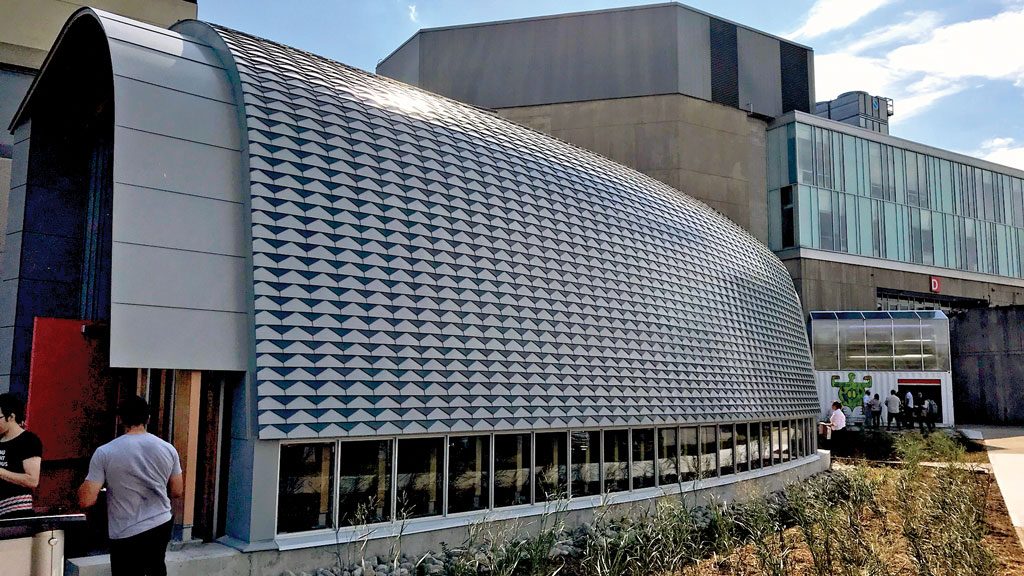

Distinguished by a “Tree of Life” roof and interior glulam beams, the lounge is a drop-in centre for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students and a venue for traditional ceremonies such as smudging.

A small link connects it with the centre’s administration wing in a renovated classroom in an adjacent building. Complementing the overall complex will be a large garden area with traditional First Nations plants such as sage and sweet grass, says Gow Hastings senior architect Graham Bolton.

Odeyto is an Anishinaabe word that can be translated to “the good journey” and Bolton uses that analogy to explain the purpose of the centre.

Replacing a First Nations office, which was no longer adequate, the centre “connects Indigenous students with their culture and also fosters cultural exchanges with non-Indigenous students.”

While the lounge is in the shape of a resting canoe, there was little rest and more than a few hurdles for the architects and its consulting team.

Not only were they tasked with designing a culturally appropriate facility, the design team and their consultants had to grapple with a host of environmental, fire code, site remediation and construction delay challenges.

“Indigenous youth are one of the fast-growing demographics in the country,” says Bolton, explaining the college’s vision for the centre grew out of the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Right from the onset of the project Seneca College wanted an “iconic” facility and there were a lot of steps in achieving that objective.

“We couldn’t be too culturally specific,” says Bolton, explaining the lounge had to incorporate and be reflective of Indigenous culture without being weighed too much in favour of any one particular First Nations group.

After reviewing a number of Indigenous structures such as wigwams and longhouses, the architectural team came up with the canoe design in less than a month. From there the schematic design progressed into the detailed design stage.

To capture the essence and form of the upside canoe, the roof and wall had to be seamlessly integrated into one element and meeting the demands of the “complex geometry” was not an easy endeavour, Bolton explains.

The logical solution was a “tried and true” interlocking metal roofing shingle, similar to what might be found on the copper and zinc clad domes and chinoises turrets of eclectic late 19th century homes, he says.

“Two Row architects suggested we could use coloured shingles to create the Haudenosaunee Tree of Peace pattern on the roof, which honours the ancient peace between the warring tribes that made up the original five nations, now six nations, of the Haudenosaunee confederacy,” he adds.

Gow Hastings took that idea one step further and created two folded and interlocking shingles that, when joined together, replicated the tree of peace pattern in the geometry of the shingles themselves, says Bolton, who created the initial design by folding pieces of paper together.

Indigenous culture also inspired the interior decor which includes 28 curved glulam beams which are symbolic of “the 28 days of the moon calendar which Indigenous people traditionally followed.”

Designing and detailing of the beams took at least three months, says Joseph Sheif, principal of Bryte Designs, a Toronto-based structural engineering firm specializing in timber.

“Each beam had to be designed differently to meet the lounge’s horizontal and vertical curvature,” explains Sheif.

If obtaining the right design balance was a challenge, overcoming the site constraints was even more so. Originally, the college’s proposed site was on the west side of what is known as Building E. Beneath that particular parcel, however, is a box culvert. A new site to the north was chosen instead.

But there were problems with the new site as well. Shortly after excavation started last November, a high degree of contaminated soil was uncovered. Excavation had to be halted and further geotechnical studies conducted. The result was construction of the lounge was postponed until early this spring. Some demolition and preparatory work for the administrative wing renovation was able to continue, says Bolton.

Combined with the centre’s unique design, the existence of the contaminated soil necessitated the use of concrete-grade beams and helical pile foundations, says Read Jones Christoffersen (RJC) project engineer Jose Polanco.

“These foundations helped to properly support the addition, meet the stringent settlement criteria and also breached the contaminated soils on the surface,” says Polanco, adding that RJC was proud to have been selected by Seneca for the project.

The college is also proud of what it has achieved, Seneca president David Agnew told participants at an official opening ceremony in September.

“As an Indigenous teaching, learning and gathering space, it’s a much-needed expansion to accommodate the important work of our staff and faculty supporting our Indigenous students,” he said.

In a reference to the meaning of the word Odeyto, Agnew noted that: “It also represents the journey our Indigenous students have chosen, coming to Seneca as a temporary stop on their life’s journey.”

Recent Comments