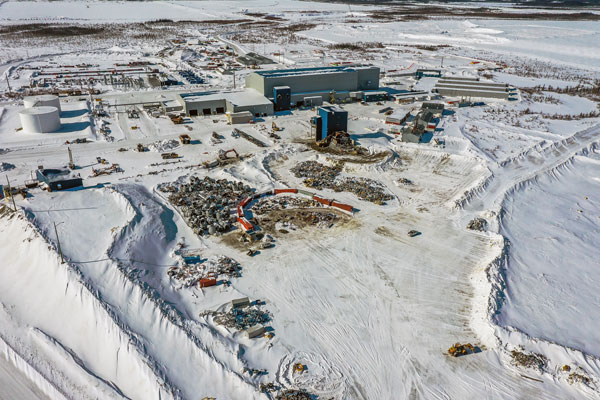

Creative thinking and utilizing both air and ice were key aspects to the success of the De Beers Canada Victor mine demolition in northern Ontario.

Despite running into a few challenges along the way, including getting equipment to the remote location, COVID-19 shutdowns and the cold weather, the demolition portion was completed ahead of schedule.

The key to success, said Enrique Bayata, general manager of Priestly Demolition Inc. (PDI) – Dakota, was over a year of planning that went into it. The project was highlighted recently during the RemTech East event held in conjunction with the Canadian Water Summit.

“That is really one of the key takeaways of a project of this magnitude is early engagement and open communication with the client,” he explained. “That is how we were able to come up with the Hercules (cargo plane) plan; that’s how we were able to come up with the schedules; that’s how we were able to do all that stuff that helped us achieve success for both De Beers and for us. Being honest, being open and planning, planning, planning from a very early stage.”

The demolition and decommissioning of the mine, the first and only open diamond mine in Ontario, was done in a partnership between the De Beers Group and PDI. Priestly was brought on board to tear down all the production facilities onsite, including about 75 structures of all different sizes from a small storage shed to a large processing plant.

Although they had 18 months to complete the demolition, Priestly finished the project after 11 months in November 2020. This past winter, Priestly used the ice road that was built to haul 4,000 tonnes of material off the site to be recycled.

“We had a lay down area where we separated the scrap materials by different types of metals: steel, aluminum, copper, so we were ready when we needed to come back when the ice road was built to remove it,” said Bayata, adding the ice road had not been built for two years. “For the stuff that wasn’t able to be recycled, we did have a specific landfill onsite which was approved by the First Nations and the Ministry of the Environment, but it was a very limited landfill so we had to really work to separate the materials and make sure we were able to recycle the absolute maximum amount.”

One of the biggest challenges was the remote location of the site. The closest urban area was Timmins, which was about 575 kilometres away.

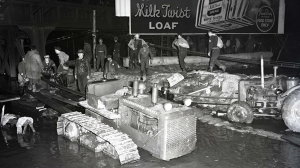

“It posed a lot of challenges of how do we get our equipment out there,” said Bayata, adding the ice road was the obvious choice but didn’t work in terms of timing. “We came up with the idea of why don’t we put them on a cargo plane (Hercules). That started a whole process of trying to retrofit our machines, taking them apart in order to be able to fit them into a Hercules plane.”

The team came up with a plan to truck the machines from Priestly’s head office in King, Ont. to Timmins and load them on the Hercules plane and fly them to the site. The demolition started in January 2020 and by March the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“We actually stopped the project for a month-and-a-half,” said Bayata. “Being in a remote location you do not want to have an outbreak. Back then we just didn’t know what we were dealing with so we decided to take a step back, come up with a plan of how we were going to be dealing with it.”

The schedule was a tight one with two weeks on, two weeks off for the crews working 12-hour days.

“We were able to meet the schedule even with the challenges that were presented so it was a successful project for us,” said Bayata, adding having in-house engineers provided the team with an advantage, especially in terms of schedule. “We were able to react very quickly, we’re not constrained to having to reach out to a third party and waiting for them to get back to us.”

When it came to working in the -30- and -40-degree temperatures of the northern Ontario winter, the team had to get creative.

“When you go into to demolish a building one of the first things you do is to cut power and all the heat was turned off on these buildings so we had to get creative on how we were going to do the demolitions, not only for our machines but for our crews,” Bayata explained.

“We retrofitted some heat cannons De Beers had. We would heat the area with these cannons, make an environment where we could have our workers work and then we would do 30 or 40 minute bursts of work.”

Areas like the old construction camps were easier to take down than other buildings such as the processing plant, which took two to three months, Bayata noted.

“That required very detailed engineering demolition plans,” he noted. “We were fortunate that it was one of the last things we did there. After we were able to clear all the insides of the processing plant then we moved into the structural demolition which is more straightforward and what we’re used to doing.”

Follow the author on Twitter @DCN_Angela.

Recent Comments