Researchers at the University of Waterloo have been using artificial intelligence (AI) technology to gain new insights that may help reduce wear-and-tear injuries on skilled construction workers and boost their productivity.

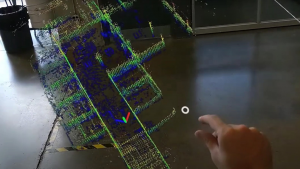

Bricklayers and masons of various experience levels were decked out in motion suits with sensors to track their movements and the load on their joints. The information was then relayed to a central database where AI programs and software crunched the data and analyzed their activities and patterns.

The aim?

To help researchers better understand the movements of the workers so they can come up with superior ways of doing the work and develop best practices for those entering the masonry trades.

The research project was overseen by Carl Haas, a professor of civil and environmental engineering, and his partner Eihab Abdel-Rahman, a systems design engineering professor at the university.

It was yet another example of industry innovation, specifically how motion sensors and artificial intelligence (AI) software can identify expert techniques that can then be passed on to apprentices.

“We got like literally a terabyte of data now,” explained Haas. “I’m not such a huge proponent of artificial intelligence, but in this case it was useful to do data analytics to try to pick out any patterns.

“We picked out patterns of movement and posture that efficient and skilled masons use and then we contrasted those with patterns that the novices use. We found that sometimes those patterns are static in terms of natural posture and sometimes they’re dynamic in terms of sequences and stuff.”

In the first part of the study, bricklayers were asked to build a wall. In the second part, masons were studied to figure out how they work so efficiently. Up to 17 motion units were installed on each suit. They were strategically located on certain parts of the workers’ bodies to accurately gauge movement.

“These motion suits are pretty flexible in terms of what you can get out of them,” explained Haas. “They literally sense the motion of body parts that they’re on.”

After studying the data, researchers came up with some interesting findings — that expert bricklayers use previously unidentified techniques to limit the loads on their joints.

“We came up with some good identifiers and some good feedback in terms of learning to help people move more effectively on the job,” said Haas. “The people in skilled trades learn or acquire a kind of physical wisdom that they can’t even articulate. It’s pretty amazing and pretty important.”

The sensors gave researchers a read on the load on joints of workers at a speed of a hundred times a second, allowing them to do a more precise and correct analysis.

Computer software interpreted the data and replicated exactly what the body was doing at the time a load was hoisted. Because researchers know the weight or the load, they were able to analyze such things as stress on a certain joint or muscle while blocks were being lifted by the workers.

“If you know what the load is on a hand or hands, the math and the software will basically tell you what the loads are on all the joints,” said Haas.

Interestingly, the data showed that the experienced bricklayers and masons in the study don’t follow standard ergonomic rules taught to novices. Instead, they develop their own ways of working quickly and safely and, in the process, put less stress on their bodies while doing more work.

Researchers discovered that, in some instances, the posture and motion used by the bricklayers on the job is actually distributing the load better than if they’d followed proper ergonomic guidelines.

The analysis of the data showed that the ergonomic rules are not always correct, said Haas, and that workers on the job are naturally finding better ways to do the work that puts less stress on their bodies.

“They have a physical wisdom they can’t articulate,” he said.

In the case of bricklayers and masons, researchers found they do more swinging of blocks and less bending of their backs to actually lift them.

“They generate motion that might be dangerous for a novice, but because of their co-ordination and experience they control it and it reduces the load on their bodies. It takes some experience and co-ordination.”

Haas said the data showed that the experienced, skilled masons are literally twice as productive as the third-year apprentices and novices and the latter two groups were putting a bigger stress on their joints.

“They were trying so hard to keep up. Masonry in particular puts quite a load on their bodies and although they keep up on the productivity curve they were really driving their bodies pretty hard.”

Haas said researchers were surprised to find that experienced bricklayers and masons were so efficient and elegant in the way they went about their work.

The challenge for researchers now, he said, is to come up with ways to help the lesser-skilled bricklayers and masons get up to speed and through that “burn-in hump” without injuring themselves, and also figure out new methods to ease the workload, stress and energy requirement.

Some aids are already being used, he said, such as elevated work platforms and self-levelling pallets that have a spring on the bottom and allow the platform to move up as bricks and blocks are removed.

“It turns out that they’re really effective for improving productivity and reducing stress and reducing the workload and reducing energy requirements,” said Haas.

“It allows a bricklayer to pick the bricks up easily and it makes a big difference because if you’re leaning over to pick up a 27- or 30-pound masonry unit from the ground and you’re doing it over and over again it takes a toll.

“It seems like such a small thing, but it makes a huge difference in terms of reducing the workload.”

Haas said researchers are still digesting results of the study and, going forward, plan to do more in-depth research that will dive deeper so they can come up with specific best practices and training.

“Maybe we can do an analysis and say, ‘Hey, if you want to save energy and your joints, do it this way.’ ”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed