It takes a lot of work to develop a construction robot from the ground up.

Some robotics researchers are applying the discipline of biomimetics to the task — letting biology supply the heavy lifting by taking advantage of millions of years of evolution to build robots that incorporate the animal kingdom’s most amazing innovations.

Researchers at MIT have explored the possibilities of RoboClam, a mechanical cousin of expert digger the Atlantic razor clam. Like its biological counterpart, RoboClam manipulates its shell to “fluidize” soil, which reduces burrowing drag. The researchers envision a self-contained, upsized RoboClam digging undersea tunnels for cable installations, or digging deep into land-based soil.

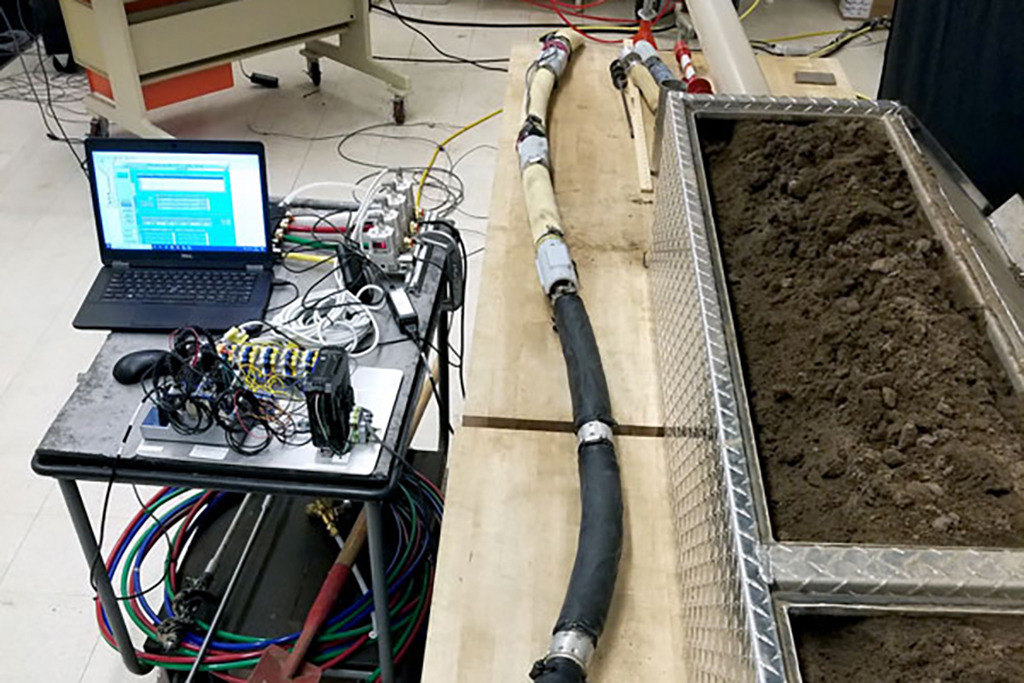

GE researchers at Penn State University are working on a project to mimic the digging capabilities of nature’s topnotch tunneller, the earthworm. The research is part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Underminer program, which aims to demonstrate the feasibility of a robot that can efficiently bore tactical tunnels to support military operations. Lead researcher Deepak Trivedi’s robot worm prototype is several feet long and uses its hydraulic “muscles” to expand, contract and move forward, earthworm-style.

His current project goal: to create a robot that can move at a speed of 10 centimetres per second and dig a tunnel 500 metres long and 10 centimetres in diameter.

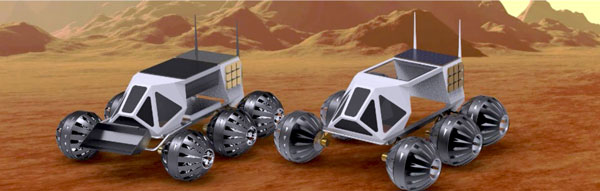

Canadian researcher Jekan Thanga, an assistant professor at the Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering at the University of Arizona, is focusing research on construction robots that can build infrastructure on the moon or Mars. But large, complex “gold-plated” robots are costly to develop and transport into space. Any malfunction in such a robot could jeopardize its mission.

Thanga’s approach? Look to nature to deliver a more cost-effective swarm of smaller and less complex robots that take their cues from colonies of ants, bees and termites working together to build complex structures.

“These robots, like the insects that inspire them, are individually simple and disposable, have limited capabilities and perhaps a limited lifespan,” says Thanga. “But together, like the science-fiction Transformers, their efforts are very robust.”

Thanga and his team are currently devising prototypes for a NASA robotic lunar or Mars base construction team that could excavate soil, sift through dust to find appropriate construction material and then produce building blocks and glass-like adhesive material using solar-heat-powered 3D printers. Sent far ahead of humans, the robots could build roadways, landing pads, utility trenches and other structures.

“The controllers that activate the ‘bots are not human programmed,” says Thanga. “Instead they are evolved using an artificial Darwinian process in computer simulation. It’s almost like breeding organisms, but their ‘genes’ represent robotic capabilities and attributes. We give them blueprints and they compete to complete them. The ones allowed to live and reproduce are those who best solve the task.”

After several thousand generations of evolution, the robots can develop co-operative strategies and act as a single entity. Each individual robot doesn’t have to achieve 100 per cent reliability.

Even at 60 to 90 per cent reliability, they can cover for each other. If one robot fails to clear an area properly, the next one can fix the oversight.

While many proposals for off-Earth bases begin with nuclear energy, the robot brigade would be powered by renewable sources, increasing their autonomy and eliminating the large payloads required to develop off-Earth nuclear capability.

Thanga, whose father is a construction engineer, says he doesn’t support the development of robots with the intent of eliminating the jobs of skilled tradespeople. But he does see potential for teams of construction ’bots on Earth.

“Our philosophy is to get robots to complete tasks that are dull, dirty and dangerous,” he says. “One task we see them undertaking is large-scale terraforming to reverse desertification. They could demonstrate end-to-end capabilities, converting seawater to fresh water, building irrigation canals, then growing grass and eventually trees to create more dense ecosystems. It would be a great project that human crews wouldn’t really want to do.”

Innovation is always burdened by conventional thinking….perhaps Nature has this solution-perhaps a symbiotic relationship or maybe this could offer alternatives in how we see—-living—-