When I first heard a proposal to integrate a network of smart technology devices into our 200-year-old home in Toronto I was skeptical. A lot of toys and gimmickry — things we don’t need but might amuse us and our visitors, so I thought.

I was partly correct about that. Since my wife Bev and I bit the smart-tech bullet a couple of months ago, we have got a lot of conversational mileage (and entertainment) out of the technology: a robot vacuum chases our dog, a talking fridge, window blinds that open when greeted “good morning” and Co detectors automatically lighting our way through darkened halls.

All amusement aside, the technology has serious merit and I can see how some of it can be an asset to commercial, institutional and multi-family residential buildings.

Low-energy consumption lights that change hue (any colour under the rainbow) and dim or brighten by voice command is a case in point.

Think about applications in the workplace: lighting optimized for a user’s workstation, simply by voice command.

For workers who are light sensitive — as a growing percentage of our aging population is — lighting can make a big difference in how productive they are.

Another benefit to the Wi-Fi-connected smart technology in our home is that it is a clean installation. This is not a physically invasive retrofit. That is a big plus for owners of heritage-designated properties who face restrictions on what renovations they can do to modernize their buildings.

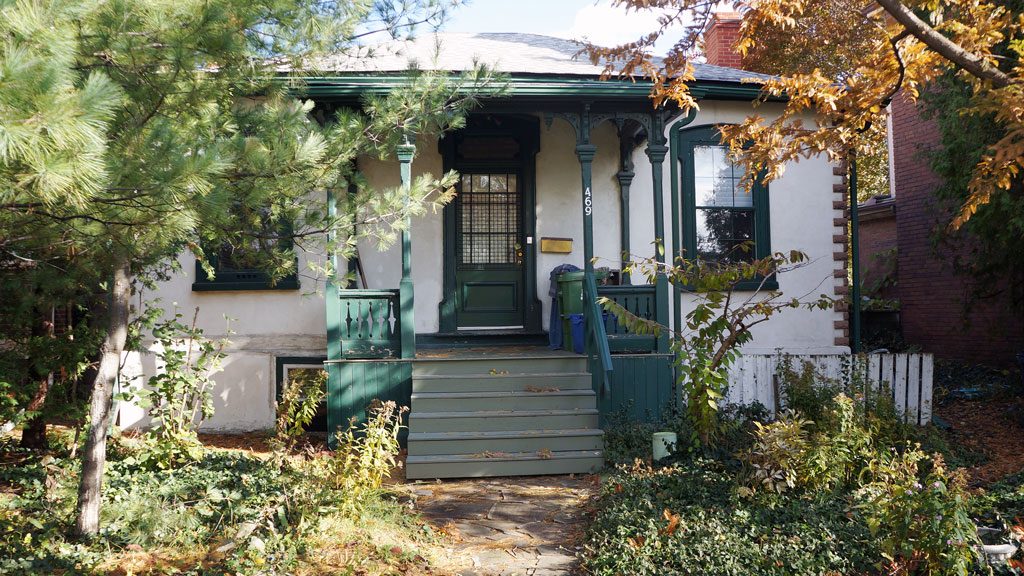

Speaking of heritage properties, our designated heritage home is listed as the city of Toronto’s oldest continuously occupied residence. Research shows the oldest part of the house — a squared log cabin — might pre-date 1800 by a couple of years.

When we bought the house almost 20 years ago, it was in rough condition. Chunks of plaster were missing from walls and ceiling, the result of years of water damage, wiring and plumbing was in dire condition and the roof, which had four layers of shingles on it, was leaking.

But that wasn’t the worst.

A cheaply built early 1900s rear addition housing the kitchen, dining room and bathroom was pulling away from the main house, exposing sizable gaps in the building envelope. When winter came and the dog’s water bowl froze solid, we tore the addition down and made the unusual choice to replace it with a salvaged early squared log structure that we viewed as being sympathetic to the original squared log house.

It was a novel design but not one that went over well with the City of Toronto’s building permits department.

“Why don’t you build a wood frame structure instead?” I recall a perplexed permit officer saying after poring over our drawings for the addition.

One of the permit department’s concerns was how to determine the R value of our log walls. A U.S. Department of Energy multi-year study on the energy efficiency of log houses helped us over that hurdle.

About 15 years later we chose to add a second floor to that log addition. The trick was to design the new addition to not exceed the height of the peak of the original home’s roof. The city’s heritage preservation services department didn’t want any building form rising above the original house, taking away from the historical significance of the property. Fair enough.

The lower elevation of the rear addition gave us some wiggle room on the design but we quickly discovered that engineered roof truss system manufacturers/suppliers weren’t interested or able to meet the squeezed elevation requirements. A crew of old-school carpenters adept in traditional roof rafter construction ably met the challenge.

After two decades we have come a long way to create a reasonably energy efficient, leak-proof and comfortable home that maintains and even accents its historic identity. But there are still things we would like to do. Time and a learned patience keep us even-keeled though.

As an experienced building conservationist told me many years ago, historic building owners are just caretakers of their properties. Don’t try to do it all. Just make sure what you do is practical to its survival and helps to preserve its historical significance for the next generation.

Good advice.

Don Procter is a regular contributing correspondent to the Daily Commercial News.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed