Winding through the north end of Barrie, Ont. and under Highway 400 and then emptying into part of Lake Simcoe’s Kempenfelt Bay, the 3.8-kilometre-long Kidd’s Creek is a cold water stream and the site of a rare marine species.

A few years ago, brook trout were discovered in a downstream section.

“Brook trout are not normally found in urban streams, so this population is special,” says Brook Piotrowski, a restoration project manager with the South Lake Simcoe Conservation Authority.

But the watercourse is also under stress. Considered by the authority to be one of the most vital creeks flowing through Barrie, it has been “urbanized” over the years through the use of gabion baskets and culverts.

This has created a “flashy” system resulting in unstable creek banks and high amounts of erosion which adds to phosphorous loading into Lake Simcoe and the silting up of potential brook trout spawning areas, he explains.

As part of a long-term strategy to reverse that situation, the authority and the City of Barrie last year undertook a $1.6-million restoration of a 650-metre-long severely eroded portion of its headwaters, an area stretching from the Lillian Crescent stormsewer outlet to Cundles Road.

“It only made sense to start from the top and work down (of the creek),” says Piotrowski of the work, which was carried out by Acton-based R&M Construction. The consultant was Water’s Edge Consulting.

As summer is the season when the water levels are the lowest, rainfall is scant and there is less risk of excavated soil entering the water, the earthworks got underway last July and continued until October.

1/2

PHOTO COURTESY OF LSRCA — This photo of the Upper Kidd’s Creek from April 2017 was taken before the restoration works started and shows how eroded the banks were.

2/2

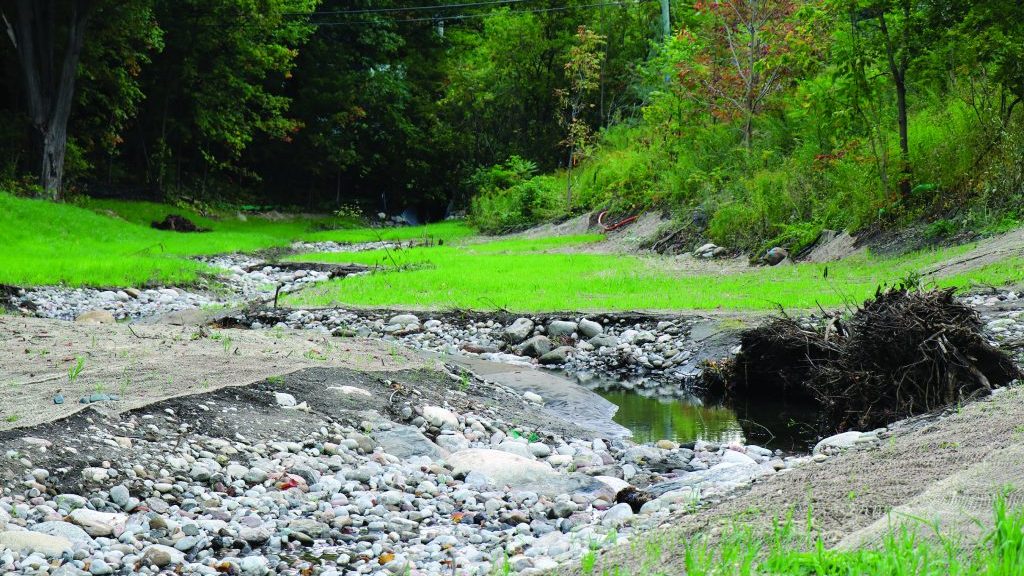

PHOTO COURTESY OF LSRCA — This photo of the restoration from Sept 2019 was taken after the restoration was completed.

Using off-road rock trucks with high floatation tires to reduce the amount of pressure on the soil, the contractor removed a number of fish movement obstacles and restored the banks using bioengineering techniques or the use of natural materials.

Included in the list of work by R&M Construction was the incorporation of felled trees into those banks for stabilization. The tree trunks were also used to create log vanes — logs strategically placed perpendicular to the creek to reduce erosion and provide cover for fish.

Another vital component to the project was the regrading and widening of the floodplain to slow down the creek’s flow during heavy rainstorms. Then, the excavated soil was used to mould three natural lookouts to provide unique points of interest to the public, as well significantly reducing the amount of earth that to be hauled offsite.

“Of the 2,300 cubic metres of earth which had to be regraded, 2,000 cubic metres was repurposed,” he says.

Asked if there is evidence if the project has resulted in an improvement in the health of the fish population, Piotrowski says it is too early to quantify.

“As bioengineering techniques were used in this restoration project, it usually takes one to two years for the plant material to mature,” he adds.

Bioengineering is one of the few construction techniques that improves with age, as the plant material matures and the roots take hold, he says.

The site will be monitored on a long-term basis and a recent inspection by city staff has shown it has held up well over the winter. At some point the project will be commemorated by a community tree planting, says Piotrowski.

The origins of the project date back to 2015 when the authority and the City of Barrie formed a partnership, followed by a two-year hydrogeomorphic assessment, or evaluation of the upper 1.7-kilometre section or “reach” by the consultant. A key recommendation was to complete the restoration in phases which, in this project, was the first 650 metres.

Due to budgetary constraints, there are no plans at this time to continue with the restoration of the remainder of that 1.7-kilometre segment, the stretch between Cundles Road and Highway 400. But there are plans to rehabilitate and improve two ponds upstream of the Kidd’s Creek project, says City of Barrie engineering project manager Jeff Henry.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed