Laurie Kennedy is the first Canuck to win the prestigious Lynn S. Beedle Award – an honour handed out by the U.S-based Structural Stability Research Council (SSRC) annually to a worldwide leading stability researcher or designer of structures with significant stability issues.

Engineering Leadership

Laurie Kennedy is the first Canuck to win the prestigious Lynn S. Beedle Award – an honour handed out by the U.S-based Structural Stability Research Council (SSRC) annually to a worldwide leading stability researcher or designer of structures with significant stability issues.

Kennedy doesn’t take the honour lightly. “It was a surprise and it is very pleasing to receive,” says the 78-year-old professor emeritus of civil engineering at the University of Alberta.

The list of Kennedy’s contributions to the world of structural engineering is long and significant.

As chairman of the Canadian Steel Building Design Committee (CSBDC), he helped ensure that notional loading would become an accepted engineering practice for buildings subject to lateral loads. Historically, the “effective length concept” was used to design those buildings but notional loading proved to be a marked improvement in structural design.

Kennedy, who chaired the CSBDC from 1966-2001, was also at the forefront of another seminal development: the CSA standard S16 called Limit States Design of Steel Structures. “It was probably what got me the Beedle award.”

S16 took five years to approve in Canada and Kennedy was at the helm of the CSBDC during the process. Adopted in 1974, it was the first of its kind in the Western World. The U.S. didn’t adopt the standard until a decade later.

Today, Limit States Design is used to evaluate all the designs for buildings, bridges and offshore structures. Before it, Working Stress Design (WSD) – also known as Allowable Stress Design – was the Canadian standard.

The problem with WSD is that it attempted to cover off safety with one factor. “You simply can’t do that,” he says.

What resulted was some structures were under-engineered and unsafe, while others were over-engineered. “Some structures were as safe as they should be but not all were.”

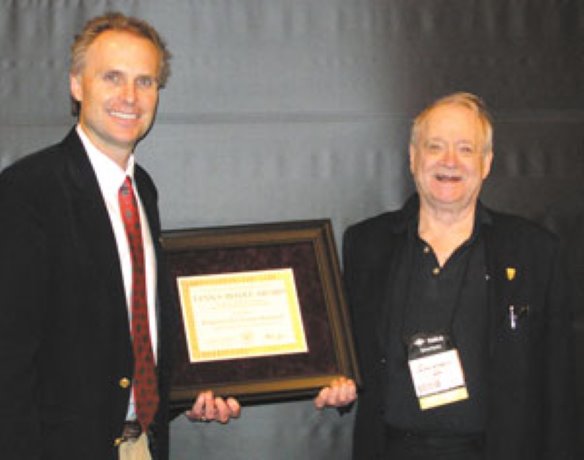

Laurie Kennedy

Lynn S. Beedle Award Winner

How Limit States Design differs is that it incorporates safety factors for both loads and resistances and how they are distributed.

“Our structures are designed better now and they have safety factors that are adequate.”

Preceding his teaching career, Kennedy was a practicing engineer. One of his first big projects was a retrofit of the Leaside Bridge in Toronto in 1966.

Then about 40 years old, the bridge was to undergo improvements to increase traffic flow that was mostly coming from the new suburban community of Don Mills. His job with Morrison Hershfield Burgess and Huggins was to re-engineer the bridge to provide more lanes and carry heavier loads.

Over 38 years, Kennedy’s teaching career has taken him to several Canadian universities and the University of Melbourne in Australia. He retired from his post as professor of steel structures at the U of A in 1994. As a professor emeritus, he supervised grad students on structural steel behavior for five years.

While his professional life has slowed – “I’ve stopped working weekends” – he remains involved in professional committees concerning structural engineering and he is a forensic engineering consultant called upon in cases of building collapse.

But the project he plans to put most of his energy into is as a consultant to his three sons who own Intelligent Engineering Ltd., a London, England, firm, that makes sandwich plate structures, a composite metal solution (steel and polymers) for various applications.

One of the company’s specialties is patented bridge strengthening and bridge repair sandwich plates.

In his spare time he enjoys watching professional sports, a night out at the Edmonton symphony and globe-trotting with his wife Therezinha.

A lot of that traveling is done with an eye for business, not just pleasure. “Work has taken me to Australia twice, South Africa innumerable times, to Europe, Great Britain and Russia.”

Kennedy says he has no regrets about his career path – a choice he made in his teens.

At 16, he was admitted to the chemistry program at the University of Toronto. After one year, however, he switched to the civil engineering program.

“I couldn’t see myself working in a chemistry lab. It’s a switch I’m very happy I made.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed