Ten years since the words “E. Coli” and “Walkerton” became synonymous in Ontario’s water lexicon, a legacy of regulatory and infrastructure improvements has resulted from construction sites to the tap.

Walkerton | 10 years later

Decade since water supply of 5,000 residents was contaminated with E.Coli bacteria

Ten years since the words “E. Coli” and “Walkerton” became synonymous in Ontario’s water lexicon, a legacy of regulatory and infrastructure improvements has resulted from construction sites to the tap.

“People have a lot of faith in their water and sewer systems — they are not front-of-mind every day,” said Joe Accardi, executive director of the Ontario Sewer and Watermain Construction Association (OSWCA).“They just want to turn the tap and have the water be there.”

“In Walkerton, people suffered, in part, because money was not spent to rehabilitate their infrastructure.”

This past May, marked the 10-year anniversary of the Walkerton water tragedy in which the water supply of 5,000 Walkerton residents was contaminated with E.Coli bacteria. Seven people died due to drinking the contaminated water and more than 2,500 became very ill. Investigations determined that the E. Coli discovered in the water indicated surface water had seeped into well water causing the contamination.

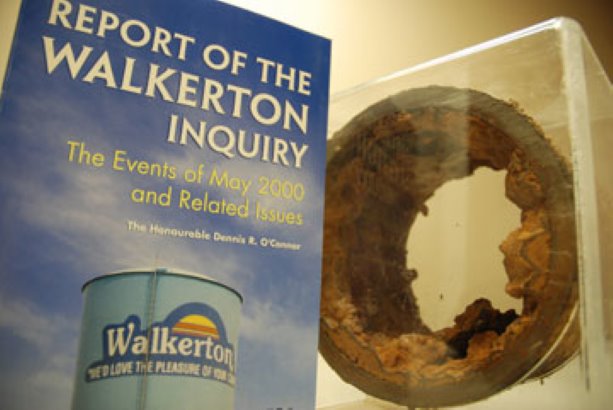

The province appointed Justice Dennis O’Connor to head an inquiry to determine how the Walkerton situation happened and how similar future tragedies could be avoided.

Ninety-three recommendations to improve water safety across Ontario were delivered in O’Connor’s Walkerton Inquiry Report.

Among O’Connor’s report findings were that up to 400 illnesses could have been prevented if water manager Stan Koebel had monitored chlorine levels daily and had notified authorities immediately about the contaminated water.

The primary source of the contamination was found to be manure that had been spread on a farm near a well.

The farm owner followed proper practices and was not faulted.

Lastly, the outbreak would have been prevented by the use of continuous chlorine residual and turbidity monitors at the well.

An aging water system also played a role in the Walkerton situation, the report found.

The tragedy raised water system safety awareness and changes took hold at sewer and watermain projects, said Accardi.

“Walkerton did a lot to open the minds of people in the construction and engineering community,” he said. “Contractors are now more conscientious, using a lot more innovative techniques to make sure watermains remain cleaner for longer.”

Material selection, project design and installation practices are three project areas that have seen the most change since the crisis.

“There is more emphasis on the pre-design than before,” said Accardi. “People are looking ahead to ensure things will last longer. Also, they are looking at materials selection to ensure they last longer.”

Installation specifications now get a closer look. Before Walkerton there were quite a few materials in the marketplace that allowed for a little bit of leakage in areas such as system joints, Accardi said.

“Now there are a lot of municipalities shying away from such materials and are forcing material manufacturers to look at items such as more efficient gasket systems,” said Accardi.

Two legislative results stemming from the Walkerton inquiry are Ontario’s Sustainable Water and Sewage Systems Act, 2002 (SWSSA) and the Clean Water Act (CWA) of 2009. The SWSSA requires municipalities that provide water and sewer services implement full cost accounting and full cost recovery. The CWA ensures that communities can identify potential risks to their drinking water supplies and take actions to reduce these risks.

Despite these progressive legislative best efforts, Ontario’s water and wastewater systems still need their aging and leaky infrastructure needs addressed, said Accardi.

“The government has done some great positive things but without concepts like reserve dedicated funding, it is very difficult for municipalities to continue their rehab programs if funding is not there,” he said.

A recent Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario (RCCAO) report found that a number of Ontario municipalities had water leakage rates of 25 per cent. As watertight pipes deteriorate, this leads to higher water losses causing higher water pumping levels. Through this diminished performance water distribution pumping costs rise and more energy is used.

“Walkerton raised issues such as the effectiveness of our infrastructure,” Accardi explained. “If someone is pumping out a 1,000 litres of water and only 700 litres make it to the customer, there is energy wasted just getting that out there.”

For some systems, up to 50 per cent of energy use could be reduced by addressing the various sources of energy inefficiency, found the RCCAO report. In Ontario, even if a 30 per cent energy savings is achieved, it can total $1.5 million per month in energy savings.

Post Walkerton legislative improvements still continued with Ontario’s recently proposed Water Opportunities and Water Conservation Act. Among the bill’s goals is to drive water conservation by reducing leaks and improving management.

“The bill wants municipalities to describe the efficiencies of their system, what the leakage rates, how much energy is used power it, how old it is etc.,” said Accardi. “It is a move in the right direction.”

Last week, the state-of-the-art Walkerton Clean Water Centre opened. The facility trains drinking water system operators from across Ontario and includes a demonstration water distribution system to offer more courses and hands-on training. Creating the centre was among the Walkerton inquiry recommendations.

1/3

2/3

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed