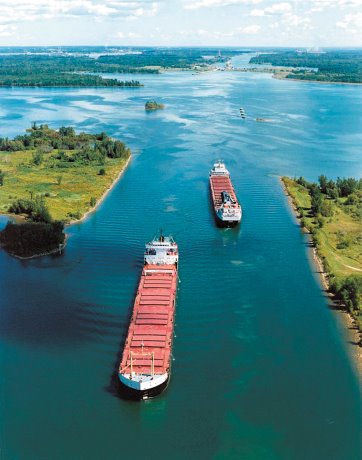

Its economic impact is undeniable, but few people give much thought to the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway System.

It allows ocean-going cargo vessels to sail to the heart of North America. It creates jobs and tax revenues. And few people realize how close Canada came to building it alone.

Mention the seaway and many people think of the entire Great Lakes system. But the seaway really reaches only from Montreal to Lake Ontario and the Welland Canal. That stretch is where the construction was done. The locks on the St. Marys River linking Lake Huron with Lake Superior were not part of the work. Operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, they are part of the Great Lakes system, not the seaway.

There had been a commercial waterway linking Lake Superior with Montreal for years, of course. It was made possible by the completion of the canal bypassing Montreal’s Lachine Rapids in 1824, and the first Welland Canal, which opened in 1833. For most Canadians, it was thought of simply as a way to get Canadian grain from elevators in Thunder Bay, to Montreal, where it was transferred to ocean-going vessels.

But the industrial expansion and population growth in the continental interior during the second half of the 19th century meant drastically increased shipping requirements, especially for moving wheat and iron ore. As a result, in 1895, the two national governments formed a Deep Waterways Commission to study the project. Two years later, the commission reported in favour of it.

A series of engineering studies followed, and, in 1909, the International Joint Commission was formed to move the project along.

But the First World War interrupted further negotiations, as well as work on improving the canal system already in place.

After the war, negotiations resumed, but it was slow going. Influential firms in the private sector in the U.S., including associations representing the rail industry, were opposed. By 1932, that opposition was strong enough to cause the U.S. Senate to reject a treaty that would have both improved the canal system and developed hydroelectric dams.

Another attempt was made with a similar agreement in 1941, and again, the U.S. Senate balked.

But support for the idea of both a deep-water shipping channel and more hydroelectric power was strong, especially in Ontario. That led to yet another feasibility study.

In 1951, the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority Act and the International Rapids Power Development Act, allowed Canada to begin navigation works on the Canadian side of the river from Montreal to Lake Ontario, as well as in the Welland Canal. At the same time, a joint U.S-Canadian project began work on a hydro facility in the International Rapids section of the St. Lawrence River just west of Cornwall, Ont. The U.S. also began work on a canal that would bypass the rapids. And for the first time, real co-operation and consultation on the elements of the modern seaway began.

As a result, in 1954, both federal governments passed enabling legislation, and agreed to proceed with the seaway. The cost would be $470.3 million, of which Canada paid $335.5 million and the U.S. paid $133.8 million. Canada would also pay a further $300 million to improve the Welland Canal.

The political foot-dragging up to that point had not been exclusively American.

When Mackenzie King was the Canadian prime minister, he had been reluctant to proceed, in part because of opposition to the project in Quebec. At one point, Mitchell Hepburn, then premier of Ontario, was successful in scuttling another attempt.

But by the end of the Second World War the patience of the Canadian federal government was wearing thin, and, late in 1951, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent informed U.S. President Harry Truman, that Canada wasn’t willing to wait for the U.S and would build a seaway alone. Parliament then passed legislation forming the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority.

The American reluctance annoyed many Canadians, and something that historians have called "St. Lawrence nationalism" arose. It has been described as a "groundswell" and it likely contributed to the Canadian decision to go ahead alone, not only on the seaway, but on the Moses-Saunders Power Dam near Cornwall.

The decision to proceed with the hydro dam seemed to have an effect on American legislators, and, in the spring of 1954, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower signed the authorization to proceed with joint construction and to establish the Saint Lawrence Seaway Development Corp. as the American authority.

One of the locks at the Moses-Saunders dam is named the Eisenhower Lock.

The key arguments in favour of the project were economic. There was a need for cheap haulage of iron ore from Quebec and Labrador to steel plants in both Canadian and American port cities. There was also a need for more hydroelectric capacity in Ontario and the state of New York.

When all the work was finished, the seaway, linked to the Great Lakes system, gave access to ocean-going ships by lifting them from sea level at Montreal through 19 locks, to Lake Superior. The largest part of that lift is supplied by the Welland Canal, where eight locks lift ships 99.4 metres over the Niagara escarpment.

Using public money to build the seaway was an idea opposed by some. The railway industry and ports on the east coast looked upon the seaway as unfair subsidized competition. Shippers liked the seaway however, although they opposed the implementation of tolls.

The original financial arrangements couldn’t cover repayment of capital debt, interest and operating costs, so, in 1977, a change in legislation converted the debt to equity held by Canada. But the new legislation required that revenues cover all operating and maintenance costs.

This has been successful, and an additional $600 million, spent by the two countries for hydro development, has been recovered through sales of electricity.

So, in the end, the economic arguments won the day. How valid were they then? Are they still valid?

Since it opened in 1959, the seaway has moved more than two billion tonnes of cargo with an estimated value of US$400 billion. About half the cargo is to and from overseas ports, especially Europe, the Middle East and Africa. The remainder is U.S. and Canadian coastal trade.

The annual tonnage averages between 40 million and 50 million tonnes.

In 2011 the seaway authority commissioned a study of the economic impact of the seaway in both Canada and the U.S. The study focussed on 2010, and showed that maritime commerce on the Great Lakes-Seaway generated 226,833 U.S. and Canadian jobs. That same commerce supported C$14.5 billion in total personal wage and salary income and local consumption expenditures in the regional economies. The system also generated $34.6 billion in business revenue for firms providing cargo handling and vessel services. This revenue was split almost evenly between the two countries.

Businesses involved in maritime activity in the system spent $6.6 billion on purchases in their respective local economies. As well, a total of $4.7 billion in federal, state/provincial and local tax revenues was generated.

There had been questions about the economic health of the seaway, but the report appears to have put an end to questions about the value of the system.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed