There are three types of wealth creation in this world, says Storm Cunningham.

OTTAWA

There are three types of wealth creation in this world, says Storm Cunningham.

Destructive wealth, or “dewealth” is derived from depleting the earth’s resources and ecosystems and replacing them with such transitory assets as office complexes and shopping malls. It’s the model that enabled the building of new civilizations, but can also destroy them if they don’t shift into a renewal mode.

Then there is preservative wealth, which derives from preserving assets and maintaining systems, while neither depleting nor actively replenishing the world’s assets.

Finally, there is regenerative wealth, or “reWealth,” derived from replenishing natural and cultural resources, by restoring, reusing, renovating, regenerating the built environment.

That’s the premise of Cunningham’s new book, reWealth!, which serves almost as a handbook for readers following up on his earlier book The Restoration Economy.

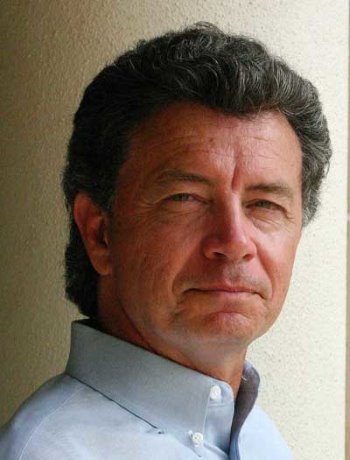

Cunningham heads the Resolution Fund, LLC, a Washington-based, but globally focused firm that helps communities revitalize their economy, environment and quality of life. He is also founder of the Revitalization Institute, a non-profit academy for community renewal and natural resource restoration.

The Restoration Economy introduced the huge and multifaceted industrial opportunity that gave the book its title. It was the first book to encompass restoration of both built and natural environments, documenting the crises, disciplines and industries that lie beneath what Cunningham sees as a global trend toward renewal.

In reWealth! he makes a clear distinction between what he calls dewealth and rewealth economies. The first depletes resources, depletes wildlife habitat, degrades the environment, and, in return, yields something called progress. In contrast, a rewealth economy restores all those things, leaving everything better than it was when we found it.

In proposing rewealth, what he is really proposing is a new economic model.

“Making our old economic model greener and more sustainable,” he said, “is like inventing a healthier form of cancer, rather than eliminating it.”

This may be one reason Cunningham has had difficulty in getting his book reviewed in many newspapers and magazines. While reaction to it has been “100-per-cent positive” from people who have actually read it, magazine and newspaper editors are bothered because it doesn’t fit into a neatly defined slot.

What kind of book is it? Is it economic theory, business, environmental, social, technical, futurist, what? It encompasses so may ideas from so many areas, it defies easy categorization, and that may be its weakness.

The principles outlined in the book apply to every level of society, from neighbourhoods up. And they can be applied without spending a lot of money. In fact, he devotes an entire chapter to how to get started when you’re broke, which comes close to describing a number of Canadian cities, including Toronto and Ottawa.

Much of what he says is based on the formation of good partnerships, but he warns in another chapter that the bad partnerships, the first generation of public-private partnerships has not yet disappeared entirely.

He also advocates more rigour in the language used to describe desirable objectives — phrases like smart growth and sustainable development. These, he said are just “warm and fuzzy” phrases that are so imprecise that they don’t mean much.

“People tend to feel good about activities that fly under those flags,” he said, “but they often aren’t clear on exactly what it is they’re supporting.”

It’s easy to put a solar array on a roof and call the building green, he said, and that’s what some sprawl developers are doing.

But when you “green up an existing property, whether it’s a brownfield site, or a historic building, or an office building or whatever, you’re renovating that building using green technologies, and you’re not offsetting all that wonderful greenness with the consumption of new materials and the disposal of old materials.”

“That’s the real green, the ultimate green.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed