Citizens of Vancouver may be more socially isolated than other Canadians, but whether highrise living is the cause is up for debate.

A report released in 2017 by the Vancouver Foundation cited those who live in Vancouver highrises as particularly susceptible to isolation.

“There’s an interesting and robust body of research that shows tall buildings have negative impacts on residents, and one of those effects is feelings of lack of belonging and social isolation,” said Vancouver Foundation director of partnerships Lidia Kemeny.

The Vancouver Foundation, one of the largest community foundations in Canada, conducted two studies on social isolation in Vancouver, the first in 2012 followed by the 2017 report. In the intervening five years, Kemeny said, research on “stranger interaction” indicated social cohesion grows when residents see people who they recognize even if they aren’t friends.

“Even a five-minute interaction with a stranger can make a significant difference to how we feel at the end of the day,” Kemeny said.

But highrise residential structures generally don’t facilitate such interactions, she said.

“In terms of the actual design of buildings, common space such as hallways, lounges, mailrooms and common areas really do influence that. They either facilitate or discourage common conversation,” Kemeny said.

Problems of social isolation can have far-reaching effects, Kemeny noted.

“Safety is negatively influenced if you don’t know people. If there’s a disaster, resilience depends on who you know and who can rescue you from rubble,” she said.

While currently occupied buildings can’t change their design, Kemeny noted a few simple steps to increase social capital in buildings.

“We’re involved in a pilot program with the City of Vancouver called ‘Hey Neighbour,’ ” she said.

She cited two different Vancouver buildings where different approaches were taken to encourage interactions between residents.

“The program identified a building in Oakridge where they identified a never-used exercise room and changed it to a common area for connecting with each other. Simple things like that can make a big difference,” Kemeny said.

Another Collingwood highrise didn’t have very much common space, she said, so events were organized in the building’s lobby and included a lobby “host” to introduce residents to one another.

“I call it ‘radical hospitality,’ but it isn’t all that radical,” she added.

The Hey Neighbour project also involves developers and property managers who also want residents to build social connections, Kemeny said.

“We’re hoping to create models of what works and what doesn’t,” she added.

“They know that when residents feel more connected to others, there’s less problems with the building. Nobody thinks it’s a bad idea, it’s just a matter of making it feasible.”

Not all involved in building design agree highrises are a factor in social isolation. Henriquez Partners Architects managing principal Gregory Henriquez called the idea that building form is a primary factor in socialization “totally misguided.”

“There are cultures all over the world living in all different forms of housing. The degree to which they’re engaged in other lives has to do with community and the shared values they have,” Henriquez said.

He pointed to other cities with similar architecture as counterpoints to Vancouver’s experiences with social isolation and highrises.

“If you look at Hong Kong, there’s no issue. In Rio de Janeiro, there’s a tradition of vertical cities that are successful,” he said.

Other cities have woven a cultural fabric through shared ethnicities and religions over hundreds or thousands of years, he added, whereas Vancouver is a new city without an established cultural structure.

“This is a tough place to come, because we don’t have a cohesive cultural fabric anymore, and that’s a good thing,” Henriquez said. “This is about an enlightened place as it exists on the planet, but you can’t expect it to have cultural depth or cohesiveness.”

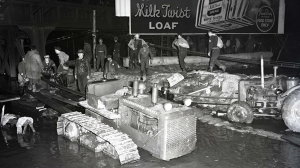

Henriquez also pointed to his firm’s own projects, such as the refurbished Woodward’s building in downtown Vancouver and the in-progress Oakridge community, as examples of community building paired with highrise living.

“These are beautiful, bold statements but they’re in the embryonic stage. It couldn’t happen in other cultures because of the things history brings. It’s a double-edged sword here, because we are way ahead in terms of inclusiveness,” he said.

“We do exceedingly well given what we’re dealing with,” he added.

Blaming social isolation on highrise housing is “one of the silliest things I could ever imagine.”

Recent Comments